Author Alka Joshi, on her best-seller, The Henna Artist

Alka Joshi only started writing her best selling debut novel The Henna Artist in her 50’s, yet ten years later, within a year of it’s a release at the start of the pandemic in March 2020, it became a New York Times bestseller, a Reese Witherspoon book club pick and is in the process of being turned into a episodic series produced by and staring Frieda Pinto. The Henna Artist tells the story of Lakshmi, who runs away to the pink city of Jaipur, in India, to escape an abusive marriage. Developing exceptional skills in henna design she becomes a henna artist to Jaipur’s many wealthy clients, overtime learning their secrets as she works to build an independent life for herself but all is threatened when her ex-husband finds her and is accompanied by a sister she never knew she had. It’s a tale of love, loss, identity, class and deceit. “I'm so glad that I waited until my 50s to start writing about characters and feelings and about our personal journeys throughout our lives because I think at the age of 20, or 30, I didn't know enough, I hadn't gone through enough experiences of love and loss and loneliness and grief and all of that, in order to be able to write about them the way I can write about them now,” she says.

And it’s true. Alka writes compassionately about her characters, even when they might not deserve it. In particular, I mention to her, the character of Samir, a philandering, entitled and über wealthy husband and architect who aids but also darkens the titular character Lakshmi’s life and Alka smiles. “I think it also comes from experiences with people like Samir,” she says. “I think we've all been there, we have all been with charming men. And the little voice in our head keeps saying, stay away from this guy. You know, this guy may be fun to play around with, but don't get seriously involved with him. He's not going to be good for you in the long term. But it's so intoxicating to be with somebody who is charming, and making you feel like you're the queen of the moment, that it's very difficult for us to stay away. And I thought, okay, I totally understand how Lakshmi could have fallen for him or have thought, oh, I think he's got my back. But on the other hand, I also understand what it is to be a Samir, and to have been raised to think that you are God's gift to the planet.”

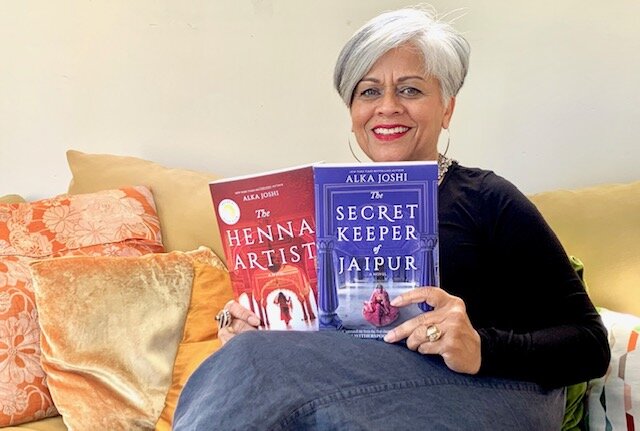

Alka with copies of both her books.

In fact, she notes, “so many South Asian men are raised to think that whatever they do is right, and all will be fixed if they make a mistake, and also that women are there to support them. They are not necessarily there to support women. And that is a point that I did want to make clear in both books. And I think in any book that I write, I think that we are all a product of our upbringing. As I got older and I'm making all of my own decisions about my career, and what I'm doing next, and the cities I'm moving to next, and whom I'm choosing as a partner, my parents never interfered. And I made mistakes along the way, just like Lakshmi makes mistakes. Like all the characters in the book make mistakes, we all should have the ability to make choices, even if they're wrong for us. And I think it's only through the mistakes that we actually learn.”

And Alka’s characters all learn because each is so flawed and she is nuanced in her portrayal of this. “I think that what I find most interesting are characters who make mistakes, and then learn from them,” she says. “Because I think that as a young girl, and especially as a young girl who was an immigrant to a western country, and completely separate from the country that I had grown up in, and suddenly surrounded by white people instead of brown people, I didn’t have any models. I think that I looked to books and to young women, to help me model how I'm supposed to be in this world. So, books were my comfort and characters who modelled behaviour for me that I wanted to emulate, were my comfort. And so that's what I wanted to write about.” Making her characters flawed she says, “was a conscious decision. And it was a reflection of what I see in life.”

Alka in front of her bookshelf.

This reflection of life includes grace given to the male characters by the female characters with regards to the mistakes they make and also within the relationships that they have with one another. A lot of South Asian women are raised to give men that grace, I say. “I see a lot of that,” Alka agrees. “And along with the grace, there is that tremendous sense of responsibility that South Asian women carry. Maybe it's not just South Asian women, maybe it's women all over the world, who are supposed to be the caretakers of their families, so we are patted on the head for being good daughters, because we are taking care of our elderly parents, we are patted on the head for being good mothers, because we are taking care of our children, even though they have transgressed, we forgive them; we go on and make a better life for them. So we're constantly being patted on the head for looking out for other people. So is it any wonder that we grow up thinking that this is our lot in life, we are meant to forgive, we are meant to forget, we are meant to excuse. And I think that there is so much involved in that, that if we were to unpack all of that, I think what we find once again, are the hands of patriarchy.”

It can take a lifetime to unlearn the positive reinforcement that comes from this pat on the head, I note. And it may be why her main character Lakshmi, like many south Asian women, blames herself constantly for life’s consequences and sees where she’s failed as a woman as the reason for the bad things that happen in her life. “I am constantly blaming myself for things that really I don't have control over,” Alka says. “And I have had to, over and over, through therapy and through talking to different people, learn that there are some situations, and the past, which I do not have control over. And yet, I am constantly berating myself for things I should have done in the past. I used to think that that was just me. And then I realised, as I talked to other women, that I think it is a female condition. I think we are trained from a very young age to accept responsibility for so many things that happen, things that we have absolutely no control over. So I'm trying to show that women do carry a lot of guilt around with them. And that guilt translates into other things. As with the women in each of these books, that guilt, I think sometimes translates into resentment, into competition between women, into anger and depression. And I have seen so many South Asian women, whether or not I know them, I can see it in their faces. There is this resignation. And the resignation is looks like, well, this is my lot in life, I have to accept it. And I think that they grow old before their time, because they are carrying so much with them all the time.”

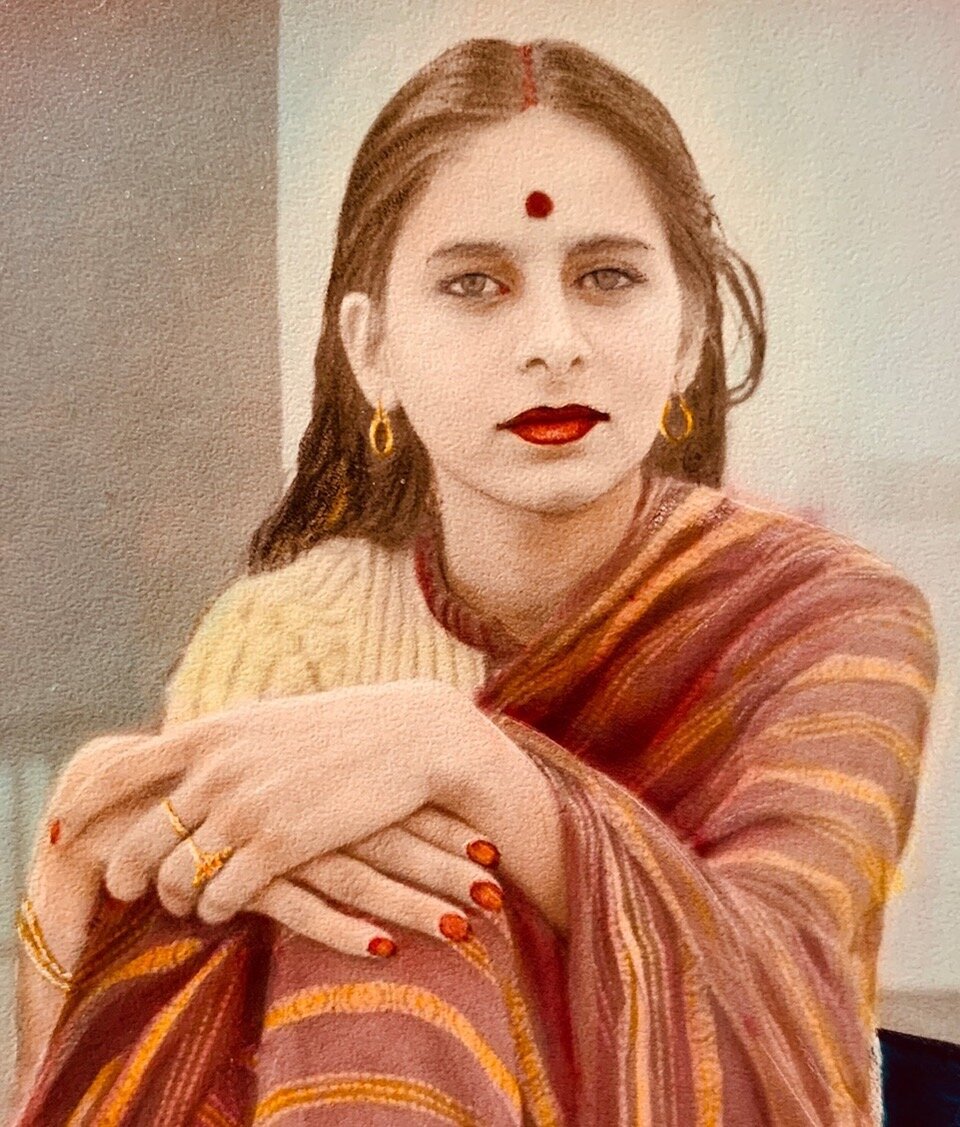

Alka’s mother painting a bindi on her forehead to celebrate her engagement to Brad (her husband’s name is Bradley Jay Owens. They were married in 1995).

Not only do Alka’s books shed light on the subtleties of a woman’s existence but they have also sparked an understanding of and appreciation of the inherently healing properties of herbs, flowers, food and henna of India through her magical and exotic descriptions of them. “It took me 10 years to realise this book into readers hands,” Alka explains, “and during that time, all the research that I had done around herbs, all the books I had read, all the movies I had seen of that era and the people I had interviewed, what I realised is that I come from this amazingly vibrant, and millennia old culture, that is rich in spices, and old, medicinal healing. I come from a culture where people have remained resilient, despite all of the centuries of colonisation and invasion, and raping and pillaging of its wealth. And I wanted to pay homage to that.”

Reflecting on her portrayal of India, Alka says, “one of the things that I have learned from the author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, is, there is danger to a single story about a person or a country. And what I really felt when I was an immigrant first here in the West, was that the danger to the India story with the West was that India would always remain mired in poverty and extreme illiteracy. And that is a dangerous perspective, because what they weren't looking at was the entire history of India, the centuries of poetry and literature, of beautiful crafts, like jewellery making, and the the weaving of fine textile cloth and the medicinal properties of the herbs that we know about with our food that the West has very little knowledge of. And I think Adichie’s advice is very well positioned especially when we're talking about nations that we consider underdeveloped, or third world, I think we really need to look at the centuries of development that came before we started looking at them.”

Alka’s mother at 19 in India. She inherited her blue-gray eyes from her mother, whose eyes were a combination of blue and green. Her younger brother also has green-gray eyes. She says this is why Lakshmi and Radha have watercolour eyes as well

Alka’a second book, The Secret Keeper of Jaipur, is set 12 years after the events of The Henna Artist and therefore looks at India 12 years after independence, the struggles it now faces and how they affect the lives of ordinary people and the decisions they make in their lives. “The second book came to me in a very different way than the first book,” Alka says. “The first book was really inspired by my mother's life and how I could reimagine a more independent life for her in Lakshmi. But the second book really came about because these characters, since I have lived with them for 10 years, they are so clear in my mind. And in the second book, Malik kept saying, ‘I've got this story to tell’.” Malik, a secondary character in The Henna Artist is a child and Lakshmi’s right hand man, assisting her in providing services to her wealthy clients.

Readers also get to see Lakshmi’s life 12 years later and for Alka it was important that Lakshmi remain childless. “So when I wrote the first book, and then in the second book, I made it clear that she's not having children,” Alka explains. “I had a lot of readers who asked, ‘oh, well, she married Dr. Kumar, will she have children?’ And I thought, you know, that's the wrong question to ask. The question to ask is, will she be fulfilled in the new thing that she has decided to do? And I think that a lot of people think that the only way a woman can be fulfilled, is if she has children. And I just never felt that way, even as a girl. And maybe it was because my mother raised me so differently, to think for myself and to know that my future was going to be my own. I knew as a little girl, I was not interested in having my own children. So I made this character of Lakshmi in the henna artist, somebody who is avoiding having children. And she knows that if she has children, especially in 1950s, India or even in the world of today, the moment that a woman has children they become primarily her responsibility. Even if she has help. She's the one who's going to manage the help. And so her life is never her own after she has children and Lakshmi knows this. So, in developing the character of Lakshmi, I was actually kind of worried that readers would say to me, hey, you know, I hate this woman because she doesn't want to have children. This is not right. You know, she is not fulfilled. But I went ahead with it anyway, because it was really important for me to have a character who decides not to have children. There are so few novels that I have ever read where a woman decides not to have children. And, I want this to be normalised.”

The author, Alka Joshi taken by Garry Bailey to mirror the above image of her mother.

It is this depth of understanding, delicate depiction of complex characters, beautiful and detailed settings and interwoven stories of love, loss and life that have made The Henna Artist catch the attention of Hollywood. The book is set to be made into an episodic series produced by and staring south Asian actress, Frieda Pinto. And Alka, is just as excited as her fans but she cautions, “the road is long, to get to the actual production. And there's many obstacles along the way, just like in Lakshmi's journey. So there is the obstacle of, which streaming service is going to lay down the money for all of the these shows that they want to do? COVID is going to impact the production because it has to take place in India. And then of course, you know, there's all of this thing about do we get the stars that we want. Now, we know Frieda Pinto is on board as Lakshmi, which will be lovely, because every interaction I have with her, she is so thoughtful, she is so serious. And, she responds to my text right away, which is super nice. And so, I love her. Michael Edelstein is the major executive producer of this and he's the one who is largely responsible for the Downton Abbey franchise. So, the moment that he read the henna artists, he said, ‘Oh my God, we could make this an Indian Downton Abbey.’”

An Indian Downton Abbey indeed! You can hear an extended version of this interview including Alka’s description of the story in the third book that she is currently working on and her advice for other south Asians looking to become authors, in our podcast episode with her on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. You can buy The Henna Artist here and preorder the second book, The Secret Keeper of Jaipur, here. Both books are also available in all good bookshops.

Alka with some of her superfans on a Zoom call to discuss the sequel, The Secret Keeper of Jaipur. There were participants from UK, Nigeria, India, Canada, Australia and the U.S. who were enchanted and engrossed in the new novel.