Why south Asians need vitamin D more than anyone else

By Dr Sefina Arif

As South Asians we hail from a unique culture; diverse in cuisine and beliefs while interwoven in language and ethnicity. Ethnicity affects health and, in our case, this is in a wide-ranging manner. We have a higher risk of conditions such as diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular diseases compared to Caucasians. We were disproportionately affected by COVID both in terms of disease severity and mortality. And several autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease are all on the increase in South Asians.

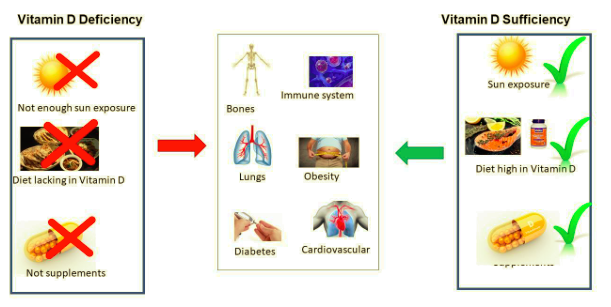

These conditions develop for several reasons. What they all have in common however, is that all of them are associated with low Vitamin D.

Vitamin D deficiency is currently epidemic in British South Asians. More than 50% of the population have a severe deficiency according to a study by Dr Andrea Darling, from the University of Surrey, who analysed Vitamin D levels in more than 6000 South Asians in one of the largest studies of its kind. Worryingly sufficient levels of Vitamin D were found in only 8% of people. These figures are alarming but not surprising given that this issue was first reported back in 1976 and since then has been regularly highlighted as a major public concern. The last few years have fuelled public interest and there is more widespread testing, but despite this, Vitamin D deficiency in South Asians is still rampant.

Plotted by author using data from Andrea Darling's study published in the British Journal of Nutrition (July 2020' Vol125 (4)

Vitamin D deficiency and health

Vitamin D is a misnomer: it is not a vitamin as such but a multi-functioning hormone that can be synthesised by the body when exposed to sunlight and it can also be obtained through diet. Levels in blood that are <50 nmol/L are considered insufficient and severe deficiency is defined as <25 nmol/L.

The symptoms of Vitamin D deficiency tend to be a bewildering mix of general tiredness, fatigue and vague niggling aches and pains which are not very specific. Indeed, people may dismiss them instead, putting them down to the part and parcel of hectic lifestyles. However, the consequences of Vitamin D deficiency, particularly long term, can be potentially serious resulting in conditions such as osteomalacia and osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is particularly relevant to menopausal women who are already at risk because of declining oestrogen levels.

Most people are aware of its key role in maintaining skeletal health but it’s the function of Vitamin D beyond bone health that is rapidly gaining traction.

Hang out in sunset hour more.

Vitamin D deficiency is associated with a staggering list of health conditions including asthma, obesity, respiratory health, pregnancy complications, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular health to name a few. Cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes both are especially high in South Asians. Vitamin D deficiency is also emerging as an additional risk factor for cardiovascular disease as recent studies show a correlation between low Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease. Similarly, in type 2 diabetes, most patients are Vitamin D deficient and low levels are associated with a higher risk of diabetes.

Why is an array of such differing health conditions associated with Vitamin D deficiency? This is because the receptors for Vitamin D are expressed widely on many non-skeletal tissues and cells in the body suggesting it has broad wide-ranging effects including on the immune system.

Vitamin D deficiency and Immune health

The role of Vitamin D deficiency in immune health became prominent during the COVID pandemic when numerous reports highlighted the link between the severity of Covid symptoms and low Vitamin D levels. Covid disproportionately affected black and Asian minorities and we now know that one of the factors underpinning this was Vitamin D deficiency. Subsequently clinical trials using Vitamin D were carried out albeit with mixed results. The general consensus however, was that outcomes were better, particularly in people who had low levels to begin with.

In respiratory infections, Vitamin D is thought to have a protective role by boosting immune cells so it’s not surprising that symptoms of low Vitamin D can include frequent and lingering colds.

Vitamin D acts on the immune system in many ways, including by regulating immune responses. When this goes wrong, when immune responses are unregulated, there is the potential to develop autoimmune disease. Autoimmune diseases are caused by misguided, unregulated inflammatory cells reacting to our own tissues. In the South Asian diaspora, several autoimmune diseases are on the increase and intriguingly are all associated with a deficiency in Vitamin D.

Researchers have looked at giving Vitamin D supplements to patients with autoimmune disease and this did lead to symptoms improving in the case of inflammatory bowel disease. It is thought that in autoimmune diseases, Vitamin D works by dampening down inflammatory cells and nurturing a more regulated anti-inflammatory environment.

Why is Vitamin D deficiency so high in South Asians?

Vitamin D deficiency is high in the UK South Asian population, but it is also high in South Asia. In India, Pakistan and Bangladesh approximately 70% of the population have a severe deficiency suggesting similar underlying causes.

There are three main reasons for Vitamin D deficiency: diet, sun exposure and a darker skin pigmentation.

Diet

South Asian cuisine is wonderfully varied with each region having its own take on traditional recipes. Unfortunately, diets in South Asian countries aren’t particularly high in Vitamin D. The Bangladeshi diet does include eating fish regularly which could account for why they have a lower deficiency compared to Pakistanis and Indians as the highest levels of Vitamin D are found in oily fish and fish liver oils.

Many Indians adhere to a vegetarian diet for religious reasons, and the staple Pakistani diet doesn’t really include foods that are high in Vitamin D which means getting sufficient Vitamin D through diet is difficult.

Recently, efforts have been made to introduce Vitamin D into South Asians diets: currently Indian TV channels are promoting Vitamin D fortified chapatti flour. This is a step in the right direction, but the diets are quite different, and wheat isn’t necessarily the staple for every South Asian diet. Other foods that are fortified such as margarine and some cereals are not routine in most South Asian diets.

Sun exposure

We get 90% of our vitamin D through synthesis in the skin after sun exposure. For a lot of South Asians, sun exposure is culturally discouraged- there appears to be an ingrained aversion passed on from generation to generation. The root of this is a complicated mix of a colourism and a colonial hangover valuing Eurocentric beauty and therefore “whiteness”.

For others, Vitamin D deficiency is compounded by religious beliefs that require modest attire which results in little or no sun exposure; this is exacerbated further in the winter months in the UK. The lack of sun in the winter months in the UK means that everyone is potentially deficient prompting the NHS to advise that people take supplements during autumn and winter.

Don’t be afraid to spend time in the sun. Your health needs it.

Skin Pigmentation

South Asians tend to be blessed with great skin but this comes at a cost: we need to spend longer in the sun compared to our fair skinned compatriots, and it is all to do with melanin.

Cells in the skin produce melanin which essentially gives skin its colour. Melanin behaves as a biological filter protecting against ultraviolet radiation from the sun. From an evolutionary perspective this makes sense as people with darker skin living in tropical areas are subjected to intense ultraviolet radiation and would need protection to prevent skin damage than those living in northern latitudes where UV radiation is weaker would need less protection.

This protective effect of melatonin in darker skinned people does have consequences for vitamin D production which means that they need to be exposed to the sun much longer, in some cases 2-5 times longer to obtain the same amount of Vitamin D as people with a lighter skin tone.

Vitamin D deficiency – The last word

It’s clear that South Asians need to be taking Vitamin D supplements, and current NHS guidelines recommend 10µg (400IU) throughout the year, but this may be higher if it is very low in the first place. Vitamin D deficiency in South Asians doesn’t need to exist, it is so easy to treat!